(This is part of the series ‘D&D: Chasing the Dragon.’ Read more from the home page.)

So I hear the question you’re all dying to ask me: “What about 5th edition?” It’s the newest version, and adoption of it seems to be high if Twitch is any indication. Everyone seems to be having a good time with it, and there’s even story and character rules in it this time! Surely it’s better, maybe the best one yet! What about that one?

To which I would shrug and say, “What about 5th edition?”

What exactly in this new hotness is a major improvement on any of the stuff I’ve talked about in this series so far? I’ve poured over the books in great detail since they came out, and I haven’t found anything to indicate that it’s substantially different from any edition previous. And really, you wouldn’t expect it to be. Such is the way of mega-franchises: change it too much, and you risk a fandom rebellion.

5th edition D&D does the thing new editions always do: it rearranges, it simplifies, it recomplicates, and otherwise overhauls the entire system to be completely and totally exactly the same as it always has been. Sorry, but D&D 5th edition is essentially just business as usual.

The Inspiration Hack

Alright, let’s just get this out of the way first. Any 5th edition apologist is going to gleefully wave about the concept of “Inspiration,” so I guess I have to talk about it. Inspiration is a new part of 5th that the designers use as an excuse that D&D is all about roleplaying characters now. Here’s how it works: you pick some kind of stereotype, known as a “Background,” which gives you some skills and gear. Then from your Background-approved list, you adopt some quirk as a “Personality Trait,” you choose an ideology as an “Ideal,” some link to the campaign world as a “Bond,” and some personal failing as a “Flaw.” If you’re feeling uninspired, you can just randomize them from the list as well.

Hey – so far so good. These are things that are at least nominally in support of the “who” of character rather than just the “what.” If nothing else, they sure as hell beat the meaningless and characterless “Physical Description” that previous editions encouraged you to have. On top of that, for the first time in D&D history, the character’s background is mechanically enforceable (insofar as the DM ever has to follow the rules). An Acolyte of some god, regardless of class, gets free healing at that god’s temple – it says right on page 127 of the Player’s Handbook. Character background finally matters in a way that gives players narrative agency.

On top of this, any time a player acts in accordance with their character as defined by this Background, a DM may award “Inspiration,” which the player can later spend on a bonus die that stacks their odds on a single roll. They can spend it whenever they want on anything they want, though they can’t have more than one at a given time. It’s a simple and straightforward reward for roleplaying.

And it’s absolutely gutless as a storytelling engine.

Like everything else in this series, the devil is in the details. You have to take Inspiration in the greater context of everything else the system is doing simultaneously. Since all the same forces from previous editions are at work, Inspiration is but one incentive among many. And hamstrung as it is, it can only pull so much weight.

Take for example this Flaw on page 139: “Once someone questions my courage, I never back down no matter how dangerous the situation.” Really? Never? So you’re going to walk straight into that Prismatic Wall? I mean, your character doesn’t know what it is, and I just asked if he’s afraid of some pretty colors. Are you ready to own up to your Flaw and barge in?

…Yeah, that’s what I thought.

And that’s just the stuff you can see or read about in a source book. Remember, your DM is keeping all kinds of secrets from you in order to foster a sense of danger and threat. That’s their job. So frequently you won’t even know exactly what is at stake when you fly into a situation, even one you know to be dangerous. The consequences may even be something the DM just makes up on the fly. Maybe you’re willing to throw yourself on their mercy the first few times, but all it takes is one time where the DM went too far. All it takes is one time where they didn’t appreciate you flaunting danger so flagrantly, or when the realism of the game “forced” them to cut you down. And after that, you’ll never look at your Flaw the same way again. You’ll start to think twice about invoking it – a reward of Inspiration won’t help you if you’re dead, after all.

Other times, acting on your Background can be a recipe for social turmoil at the table. Consider “I turn tail and run when things look bad,” one of several Flaws that involve running from fights. In a game that’s all about fighting and the consequences of those fights, it’s only a matter of time before the player bails on their buddies only to have one or more of them die. Are you sure you want to be the DM who watches the ensuing argument and finger-pointing – and then awards Inspiration to the defector? Yeah, game probably isn’t happening next week.

Some Background aspects are just plain weird in the context of the D&D structure. “I have a ‘tell’ that reveals when I’m lying,” from page 130 seems simple enough at first glance. But then when it enters play, all kinds of D&D expectations and conventions come up. Remember, the theory behind Flaws is that the player should voluntarily roleplay in certain ways and is then rewarded with Inspiration. So since you have this Flaw, are you expected to invoke it every single time you lie? Or can you simply choose to ignore it when you’re telling a lie you really want to sell? Is it really a character flaw if it only comes out when you feel like it? Remember, your instinct as a player is to make things go well for your character, so you’ll think twice about anything that does the opposite.

So should the DM fix this? Can they make you invoke this Flaw? Should they make you roll for it? What’s the roll? Do you still get Inspiration if you were forced to invoke this Flaw against your will? And does it still count as “good roleplaying” if someone else had to force you to do it? The ambiguity of how exactly this Flaw works in real play gives one the impression that as the designers sat around brain-storming three-hundred-odd Background Traits, they just weren’t thinking that hard about each individual one.

But then that’s the reason Inspiration is so weak as a story engine. It’s not an intricate and nuanced system specifically and painstakingly crafted to pull players consistently in one direction – it’s a hack that designers threw on top of a preexisting game. It’s not a critical part of the system by any stretch, and the Dungeon Master’s Guide even lets DMs completely ignore it if they want. That’s how little it matters.

See, if you remove Inspiration and Backgrounds as game rules, the rest of the game system will function perfectly well. Nothing really needs to be in those blanks on your character sheet because nothing else really depends on them. If you have them, that’s nice, but it’s not part of a greater overall system that takes an active hand to shape the game.

Now try to remove “Dexterity” as a game rule. Instantly the whole game system unravels. Several different skills key from Dexterity, you gain bonuses to hit and damage with some weapons, you can use it as a source of AC, you use it to roll for initiative, and on it goes. Many parts of the game system rely on characters having a Dexterity score, and a character without one is plainly incomplete. Viewed from that perspective, it’s obvious which parts of the system are important to D&D, and which ones aren’t.

And even when Inspiration is present and functioning, it’s still functioning through the lens of the D&D condition. The power dynamic of the DM/player relationship features heavily into how it plays on the table. The fact that the DM is the ultimate source of all Inspiration invests a lot of privilege into just one player. It’s the DM’s opinion of good roleplay that’s most important around here! And by strategically choosing when and when not to award Inspiration, a DM can even use it as yet another way to control player behavior. The Dungeon Master’s Guide even says as much!

Perhaps strangely, Inspiration actually reminds me of AD&D from 1979. Did you know that back then, AD&D mechanically authorized DMs to withhold a level-up from you if they didn’t like how you played your character? It didn’t matter that you reached the XP threshold for level six – if you weren’t an appropriately brave fighter or a “thiefy” enough thief, or whatever subjective bullshit the DM made up, you might find it extremely difficult to get your level! It’s the DM’s game, and you’re there to make the DM happy.

I wasn’t kidding when I said that the structural foundation of the game hasn’t changed in all this time. Each new version of D&D just has a different way of expressing it, and Inspiration is no exception. It’s not even very much different from what many players were already doing on their own when they offered bonus XP for subjective roleplaying. By giving the opinion of the DM disproportionate value, it drives the old, familiar dynamic that a good story is “one that the DM likes.”

In all fairness, Inspiration isn’t nothing. It’s actually kind of nice to see something as established and mainstream as D&D take its first shaky steps towards narrative shaping. But those steps are taken atop all of these historical traditions and faithfulness to the original. It’s still hopelessly mired in all the old trappings and pitfalls. It’s stuck – player expectations require that D&D have a certain baseline similarity to how it’s always been, or they’ll rebel. But the parts recognizable as D&D pull against the new roleplaying parts so hard that it leaves me with the impression that these storytelling rules are simply in the wrong game. When you’ve seen what a real storytelling game looks like, something built from the ground up to pull exactly one direction and hard, D&D’s iffy little hack just feels underwhelming.

Realism 5.0

The things that are really important to 5th edition are the same things they’ve always been. All it takes is a little bit of reading between the lines, and it comes out plain as day. Is there a chase scene? The 5th edition rules for that seek to quantify all the things you might see in a movie chase scene, but filtering it through the D&D method means that the highest priority is realism. People can only run as long as their Constitution score holds out. They can only hide if they break line of sight. That’s just physics!

To hell with physics. I want a good story. I can easily come up with a plausible and realistic physics-type justification for any story outcome – I don’t need help with that. What I need help with is deciding what the best outcome for the story will be. How about some rules for bidding on the conflicts that are most important to me as a player? How about an ebb and flow of success and failure? How about a success that requires me to also take on a complicating plot element? If nothing else, how about an acknowledgment that if players don’t catch their quarry, the story grinds to a halt more often than not? Nope. Gotta be realistic. Everyone’s got a Con score, and we’re gonna use ‘em.

This obsession with realism has a way of treading on players’ ability to participate in the story. Often the game betrays them even when players play by its rules. Page 178 of the Player’s Handbook has a particularly aggravating technicality in the name of realism when it discusses searching for hidden objects. Say that a character is searching a small room for a key. The player’s tool for doing so is a Wisdom (Perception) check, which is rightly understood as a layer of abstraction. See, a player can’t be expected to specify every single poke and prod of a character’s search – the ability check is meant to encapsulate all of those into one roll for the sake of expediency.

But then the book goes on to say that if you don’t specify that you’re searching the part of the room where the DM hid the object, you have no chance to find it at all. After all, the key is in the dresser, and if you didn’t say you were looking at the dresser, it wouldn’t be realistic to find the key! Really, D&D? You can’t just honor my intent that I’m searching the room? You give me a tool of abstraction to solve my problems, and then you double-back on that abstraction and want me to be specific after all? Would it be so terrible if I found your damn key?

I really can’t stress enough how destructive this dedication to realism truly is. I’d go so far as to say that it’s the single defining feature that separates D&D-likes from storytelling games. Either you intend your rules to be about simulating a world, or you intend them to be about generating a story. There really isn’t a middle-ground, because those two design directions are on different layers of detail.

Storytelling games consider the overall narrative direction as a whole, taking on a bird’s-eye view of what is happening and where the story is heading. When such games interact with plot and narrative, they do so in broad strokes. When the system adjudicates a conflict, that conflict is defined and resolved in terms of the characters’ ultimate goals for the entire scene. It glosses over the specific, fiddly ways they try to achieve those goals in favor of a wider narrative approach. It then evaluates the conflict using mechanisms that codify the rules of good storytelling, and this provides a framework to help players tell that story in the abstract.

The narrative element comes first: only after the game determines what is going to happen do the players worry about why or how. When using this method of conflict resolution, players often find out what is about to happen in the scene rather than watching it happen in real time. Once they know how the story is to proceed, once the system sets up the scene and its outcome, they honor that outcome as they play that scene out, and they are free to invent the individual details that make the story happen that way.

Games like D&D are the opposite. They exist one layer closer to the action. They’re far more concerned with the cause and effect of the events than what they actually are. Conflicts are framed as individual moments of step-by-step actions rather than the overarching goals those actions serve. Simulator games don’t care why you’re doing anything, just that everything you did was sufficiently realistic. In fact, these games aren’t much concerned with anything other than what’s happening in this individual moment in time. “This character died because he didn’t have enough AC to avoid being bitten by a dire wolf, which deals 1d8+10 damage, and he only had 11 hit points because he was a level three wizard with 12 Constitution, and that’s why he died. See? I proved it!”

It doesn’t matter to D&D that said wizard was a dethroned prince trying to win back the hearts of his people, and that this particular ending is rather… abrupt. That just isn’t the layer that D&D is concerned with. D&D-likes get lost in the details of simulation by paying close attention to every single minor happening to ensure its individual realism. With such a low-level focus, simulators simply can’t care about the broader narrative. They can’t see the forest for the trees.

The All-Game Fallacy

For all the effort 5th edition puts toward being about storytelling, it’s really out of place in a game that’s fundamentally a simulator. The designers seem to think that all of these things can exist in the same game instead of being on the different levels of detail that they are. Trying to be all things to all people isn’t a new idea for D&D, which has featured discussions of player types in several Dungeon Master’s Guides at this point. But by trying to rope all these different interests into the same game, the design of the game often doesn’t know what it wants to be. And 5th edition is no exception.

The 5th edition Dungeon Master’s Guide says in no uncertain terms that slaughtering the party with a random encounter is an unsatisfying ending for players. And yet you can find instant-kills all over the place in the book. The Talisman of Ultimate Evil conjures up flaming fissures to utterly destroy a character on a single failed save. The Bag of Devouring pretends to be a valuable item, and literally eats characters, killing them with no saving throw. An example trap is a statue’s mouth with a Sphere of Annihilation that vaporizes you if you climb in, and the book suggests coupling it with a spell that compels you to do so (You wanna take that “foolish courage” flaw now?). An acceptable property for an Artifact to have is to instantaneously age the character, making the character make a saving throw, or die from the shock and hand your character sheet over to the DM to be played as a mindless undead. That’s a lot of instant death you got there, 5th edition!

So which is it? Should I throw capricious, sudden death at the players or not? You’ve given me all these tools to bring character stories to a swift and brutal ending, so you clearly want me to use them. But when is an appropriate time to do it? The source books are silent on this front. Is it “up to me?” What if I get it wrong? Help me to play your game. But, as usual, 5th edition hides behind the “different strokes for different folks” excuse, trying to pretend it can satisfy any type of player and play any type of story. And so we’re back to the paradigm where the game leaves the heavy-lifting at your feet.

In that way, 5th edition maintains D&D as a game of mismatched expectations. See, you might think that the solution to all this is “being a good DM.” But the fallacy there is that no one really agrees on what being a good DM is, what the “right” way to play D&D is, or who the best kind of players are. Opinions vary wildly between differing communities, different generations of players, even between people in the same D&D group. Dungeon Master’s Guides try to pretend that grouping all these disparate interests together under the same story is normal – a suspiciously convenient position to take when it means you get to sell your book to literally everyone.

But in the real world, these interests are often pitted against each other. Each player having fun in their own way is only good until the dungeon slayer gets bored of all the court drama his friend is doing, kills a noble, and gets them run out of town so that he can find a dungeon to plunder. Maybe that sounds like bad behavior, but if you stop him from doing it, someone’s still not having fun! What happens when the thespian is waxing a little too poetic? What happens when the power-gamer is too powerful? What happens when the instigator starts too much shit? How do you even define “too much” for any of those?

The 5th edition Dungeon Master’s Guide, just like the many before it, leaves the issue of player wrangling to the DM. But let’s not pretend that the DM is a neutral party in all this. The DM has their own thoughts, preferences, and biases, and as the one with the most power by far, those predilections will go on to define the game over and above anyone else’s. Those playing the way the DM likes will get the most attention and support. Those playing other ways will be tolerated at best. That’s the inevitable result of a group all pulling in different directions. The best case scenario is a polite patience as each person indulges what they came here to do, usually by themselves. And the worst case scenario is very ugly indeed.

So if the solution to all this is “be good at D&D” in a vaguely defined way that nobody agrees on and that the book doesn’t prescribe, then we have to conclude that the game is setting up its players for failure. If the players end up in messy social situations and mismatched expectations as a matter of course in the game, that doesn’t sound like a well-designed game. Excusing the game in favor of blaming “toxic players” ignores the realities of the systemic forces that push players into those behaviors. If you change the system, you change the players. Let’s think about doing that before we start condemning people wholesale for not living up to our ideals of how the game “ought” be played. After all, someone out there doesn’t think you’re playing the game right either.

“Fixing” D&D

So how do you fix D&D? The simple answer is “you don’t.” Trying to turn D&D into a storytelling game isn’t something you can accomplish by simply piling more rules on top of it. And if you try to alter the foundations with new ones, the result that comes out the other end would be so unrecognizable that you really couldn’t call it D&D anymore. Trying to market something like that under the same name would just be dishonest. I mean, just look at how the “old guard” responded to 4th edition, which is still very close to D&D in the grand scheme of things.

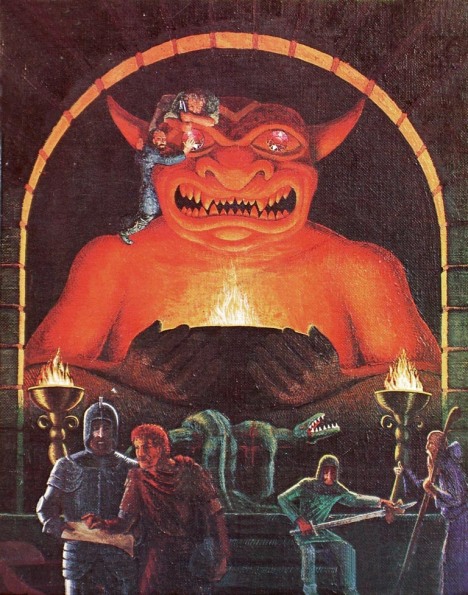

But it goes beyond “you don’t” or “you can’t” – really, you shouldn’t. Because (twist ending) D&D is already a storytelling game – just not the story you’re probably trying to use it to tell. The men who wrote the foundational rules of the game – rules which largely still exist in current editions of the game – had their own idea of what a good story is. And you need look no further than the cover art to AD&D to understand what that story is.

Here we see a group of armed thugs invading the cultural temple of some lizard men, hacking them to pieces, and defacing their god’s statue to plunder it. Are the lizard men evil? Did they deserve to die? There doesn’t seem to be any indication that there are even good or bad guys here. From the body language of the killers, “heroism” doesn’t factor in at all. This is strictly business. Ideology is absent. There is only the logistical challenge of pulling off this latest murderous heist. Maintain the gear, pry up the jewels, update the map, figure out where to go next. The vermin have got to have a hidden treasure cache somewhere.

This is what D&D is all about – the designers made it that way! This is their vision for the game, front and center. It’s pulp-fiction sword and sorcery. It’s Conan stealing the treasure. This is what the rules govern, and this is where they’re most at home. You can roleplay other things if you really feel the need. You can be, as Gary Gygax would put it, “a wanna-be community theater actor.” But the game doesn’t really care if you roleplay or not. That’s because from the perspective of the game you’re never not roleplaying. When you murder something and take its stuff, that’s exactly the person Gary wanted you to be. That’s the story he wanted D&D to tell. That’s the inspirational roots of the game, and we’re still largely playing by the same rules today.

That really casts that old distinction between roleplaying and “rollplaying” in a new light. As the roleplayers sit around character-acting up a storm, dice untouched, books unopened, they do so because they’re trying to tell a different story than the one Gary wanted. If they were telling Gary’s story, if they were killing things and acquiring plunder, it would only make sense to start rolling dice. That’s exactly what the rollplayers are doing. By rolling dice, by engaging with the rules, they’re not ignoring story. They’re absolutely telling a story – just a different one.

From that perspective, there was never any such thing as rollplayers at all. They’re just people who play the game as intended. It’s not a “lesser” form of play – it’s just the game played straight. The self-labeled roleplayers aren’t playing the “real” game – they’re not playing it at all! They’re rebelling, refusing to interface with the game, and insisting that it be something else. They’re not happy with being Conan the plunderer, so they tell their own story in free roleplay, a story they could’ve told with no rules or books. After all, the ones they’ve got don’t address the story they want to tell. That doesn’t mean they’ve “matured” as roleplayers – it just means they’re in the wrong place.

So no, you really shouldn’t try to fix D&D, no more than you should try to fix a hammer to turn screws. It’s already working as intended, and the things you would need to change about it would just ruin it in terms of its original purpose. Maybe there’s merit in trying to make a better hammer, but there’s no need to frankenstein a functional design just because you don’t like what it was originally designed to do. It’s better to state your own purpose and build something new from the ground up, tightly focused on your intent.

It bothers me when I read a game review for a tabletop RPG, and the author says that a given game won’t handle stories outside of a certain genre – as if that were a drawback. Really, it’s the single-purpose games that are often the best. When you’re fully committed to exactly one type of story, you can deliver on the story that much more definitively. When you don’t have to worry about trying to be anything else, you can be truly great at the one thing you can do.

On the other hand, if your game is trying to be too many things, you end up in a situation like the one in which 5th edition finds itself: a Dungeon Master’s Guide filled with half-assed, optional frankenrules that merely pay lip-service to the alternate genres they try to emulate. You end up with things like the madness rules, where a DM at their whim decides to randomly roll for a madness effect, whose most relevant impact is combat debilitation, and which is instantly cured by a second-level magic spell. Not exactly The Shining.

Or how about the honor rules, where the DM makes up a code of behavior, becomes the sole arbiter of whether or not you’re following it, and rolls dice to try to make you break the code unintentionally? Is this the makings of a dignified samurai story, or is it more like the social posturing of a high school bully?

No, if there’s a way to make D&D better, it’s by making it more D&D. Focus on the core values of the primary experience and find ways to deepen them. Maybe that looks like what Matt Colville did with Strongholds & Followers, an expansion on the 5th edition rules for establishing and maintaining a base of operations and its population. Maybe it involves a more mechanically-precise and tactical combat system to develop the game’s strategic depth. Maybe the way forward is to help organize the many DMs’ maps and dungeons into a single world, and facilitate the player characters traveling from game to game in order to visit and adventure in another DM’s milieu. Maybe it looks like something else entirely.

But whatever it is, let it be D&D at its most pure. Instead of trying to bend D&D to some other purpose, leave it to do what it does best. Fulfill your other purpose with something new, custom-built to get it right. No need to build over the top of an established game designed for something else. I know it’s intimidating to have to start from nothing with no existing structure to build on. I know it’s tempting for a designer or publisher to leverage an existing brand. It’s even more tempting for players to just play what everyone’s already used to.

But the best things are often only good at one thing. It takes designers a lot of effort and creativity to make them. It takes players a lot of effort to find and learn them. Heck, it takes effort to get your friends to even try them. But once it hits the table, a tightly tuned, single-purpose game is worth it – every bit.

I’ve read through the entire series, but I think this is the particular entry where the comments I want to make really fit.

The thing that really frustrates me, and really makes me shout at the monitor, is this equivalence you draw between NARRATIVE and STORY. The central conceit seems to be that if your system does not mechanistically encourage participants to create an overarching story structure, complete with ratcheting tension and a denouement at the end, then it should not be relied on for storytelling and instead should be considered more like a strategy game than a role-playing game. To this end, you sort of posit this dichotomy between “Simulators” and “Storytelling games”–after all, how can you get a nice, fulfilling catharsis that comes from overcoming impossible odds if those same odds are explicitly spelled out and ACTUALLY impossible?

To me, this is a very limited and narrow view of how storytelling through the medium of games can work. I would agree that the source material from D&D and dandy-likes are misleading and waste many, many words telling you can use them to create such structured narratives, but I strongly disagree with the notion that they are somehow hobbled in the ways they can generate role playing and/or stories at the table without relying on Rule Zero or in some other way wholesale abandoning the rule books.

For example, let me use my first campaign I ever ran as a DM–Numenera, which almost certainly fits into the D&D-like category (it is from Monte Cooke, after all). I used one of the pre-built dungeon crawls as a launching off point. The players are exploring the carcass of an ancient alien ship, and then turned the thing on (something that wasn’t accounted for in the module, but hell if they didn’t roll a 20). Adventures ensued, wherein they went to strange new places and alien new worlds, and basically just sort of faffed about in a Star Trek sort of style.

There was no central plot. Hell, there was hardly any real conflict. The closest thing to a climax was when they figured out the “strange new world” they had been inhabiting in was a great mechanical beast that was currently on a Kaiju-esque mayhem spree, and through some lucky rolls they actually managed to escape the thing without dying (well, most at least).

The whole ordeal broke probably every rule for crafting a proper narrative. I killed one of the characters in the first session (“NOW we’ve broken him in as a GM!”). You decry simlationist rule-sets and bloated campaign settings, but my example above is essentially one big sprawling meandering thing that grew out of me saying “YES, but…” to the players within the constraints of the actions they took to change the world around them. All those rules and setting details gave me the TOOLS to say “YES, but”!

I followed those same mechanical rules you say are the antithesis to story, but you can’t convince me for a second that we weren’t generating a collaborative story, it just didn’t have a three act structure.

I never said you can’t have a good time playing D&D-likes. I’ve done that. I never said you won’t end up telling the story of that one time you played a D&D-like. I’ve done that, too. I haven’t even said that you can’t tell a story with D&D books sitting on your lap. I’ve done a hell of a lot of that.

What I’m saying is that simulator games have no idea what a story is. This is different from saying they don’t know what a good story is. It’s more of an indifference to story altogether. There’s nothing baked into their DNA that recognizes that there’s a story going on. All it knows is what’s going on in in this one exact moment in time, and the way it decides what happens is a combination of realism and randomness.

So when your game is what amounts to a physics engine for some particular setting, you don’t have a storytelling game – you have a game that you later tell stories about. And that makes a bigger semantic difference than you might think. Because if “games we tell stories about” are storytelling games, then there is no such thing as a non-storytelling game.

I have all kinds of stories from my time spent playing DayZ – narrow escapes, foolish plans, volatile situations, you name it. But I’ve never heard anyone call DayZ a storytelling game. It’s a game you tell stories about after the fact. You don’t really know precisely when a crazy story is beginning or ending – you’re just playing the game, “faffing about” as you say, until randomly some crazy chain of events unfolds. And then later on you tell someone “Oh man, you won’t believe what happened in DayZ last night…”

That’s what a story is: a distillation of a series of events down to just the most relevant parts. You don’t relate every last moment of your play session – you can’t, that’s way too much. So you skip over parts that weren’t important in order to get to the good part, all the while making sure you’re giving enough context so that your audience understands why the good part is so cool.

That’s what happens in D&D-likes. You faff about, looking for something that looks cool or fun, and eventually some stuff happens that you later reformulate into a story. The game didn’t know you wanted a story – it was just making sure the world kept turning. It was you who decided that a story happened. And you probably won’t even tell the “whole” story, just the parts that were interesting enough to tell someone later on. So on the whole, it’s not much different from any other game. Or even just living life.

I’m not going to tell you your Numenera experience was a bad story – I have no idea, I wasn’t there. I’m definitely not going to tell you that you didn’t have fun – obviously you did. But I challenge your assertion that a “story” resulting from your D&D-like is somehow special or unique. Stories as a byproduct are inevitable for literally any temporal activity.

I also think you’re putting undue value on the word “story.” D&D-likes don’t have to be in the business of “crafting stories” to be fun or important. That’s not what they’re for. If they were about stories, they’d have rules that address narrative, plot, tension, and resolution. Instead, they have rules about world simulation. DayZ doesn’t give me tools for “Yes, but…” It gives me guns, area voice chat, and a world to run around in. And that’s fun all by itself.

I recommend you read this thread from Matt Colville’s subreddit. Matt asserted on Twitter, and writes further in that thread, that D&D isn’t a storytelling game. Bear in mind that Matt is an author, a game designer, and a huge proponent of D&D. He’s well positioned to know what he’s talking about here, and he doesn’t have it in for D&D. He’s simply being honest about what the game is and what it isn’t. He directly addresses the insecurity that a lot of people seem to have about the hobby. Those folks like to throw around words like “narrative” and “medium” because they feel important.

Matt writes: “I am not saddled with that complex. I feel no need whatsoever to try and elevate D&D into anything. I feel no inadequacy at the fact that D&D is my main hobby. I don’t feel the need to apologize for it, or trick people into thinking it’s something it’s not.”

So if you liked the story of your Numenera game, good. But the degree to which it was a good story is the degree to which you the players made it that way. In fact, if you’d played with the setting alone and no rules, you would probably have been just as well off. Hell, you probably had sessions like that where the rules hardly even came up. That’s because the game isn’t designed to help you with story. It has no idea what a story is.

Thanks for reading!

Upon reflection, I really should have let my ideas bake before posting. I strongly agree with a lot of the arguments you make, but I have issue with your conclusion, and every time your restate your thesis it’s like a little phantom finger is poking me in the ribs. I should have given more space to let the phantom fade because what came of it is a really unclear criticism on my part. I don’t think you’re attacking my “fun,” and honestly I don’t really think “fun” is a part of this discussion.

Where my issue comes from, is that all the places where you talk about systems that encourage or discourage “storytelling,” what I think your REALLY getting at is “immersion.” The point of all the techniques and structures we have for creating compelling narratives, are to draw in an observer and make them empathize with the characters in their struggles. As you watch “A New Hope,” you KNOW Luke is going to triumph. Even as his friends get shot down around him, even as his dark space wizard nemesis is hot on his six, even as he TURNS OFF HIS TARGETING COMPUTER OMG LUKE WTF we know the Death Star is a goner. There’s are all sorts of bonkers logic that brings the narrative to this point which doesn’t really hold up to close scrutiny, but we still feel the tension as the climax approaches, and we still feel exhilarated when good triumphs over evil.

To my mind, this is what storytelling games seek to recreate. That’s why “what happens” holds precedence over “how it happens”–you’re recreating that same narrative structure that keeps us on the edge of our seats in the Death Star trench run, where everybody knows what’s going to happen but the details you fill in keep everyone invested. I 100% agree with you that if you want this sort of experience out of a D&D campaign you are not really playing D&D. D&D is terrible for creating these sorts of stories, and people who think it supports what I would call “narrative storytelling” would be better served by finding a different system to work with.

HOWEVER, I would argue that any time you are invested in a character, any time you feel the sting of their setbacks and the exhilaration of their victories, you are still essentially “storytelling.”

My very first role-playing experience was monstering for a boffer LARP–me and 10-15 other nerds would go out into the woods and hike for half a day, as the GM set up encounters between the forces of darkness (my group) and the 3-5 adventurers (PCs) in a very D&D-like fashion. This is about as “simulationist” as you can probably get without a holodeck–I mean, it’s not like the GM can fudge the laws of physics.

I don’t think I can recall a game that didn’t wind up going completely off the rails for what the GM had planned by pure happenstance. By your definition, this game was terrible for storytelling. However, I think that overlooks the real investment each of the participants had in their characters. Everyone was fully invested in the struggles their characters were facing because they were actually physically struggling, rather than because the narrative gave them a proper climax and resolution. It’s the same goal with a different path.

To my mind, D&D (and it’s ilk, because I really don’t think D&D is even the best system in this regard) is all about giving you that same sort of experience. It’s all about putting you into an orc suit without requiring you to go hike in the woods first. It gets you invested not because of stakes or climaxes or any of the other things that make well constructed narratives highly effective, but because you ARE the character. What you wind up with then, are a bunch of “stories” that only work as such because you have to be there to feel the investment.

Summarizing D&D as a tactical board game where any roleplaying happens external to the RAW is like saying the people in my LARP were all just nerds looking for an excuse to beat each other with foam weapons. You can’t take a transcript from a properly run campaign and turn it into a Broadway script, but in the moments where the players are invested in their characters–where the players empathize with their characters plights–those still capture the essence of storytelling and roleplaying.

I don’t think that I’d say that players going off the GM’s rails is bad for storytelling – in fact, I’d say that rails miss the entire point of doing something together. If a GM wanted to “plan” something, they should just write a book, which is a worthy endeavor by itself. But if there’s going to be more than one opinion about how this story goes, “plans” and “rails” are wholly inappropriate.

Players jumping the rails of a GM’s plans doesn’t by itself create a bad story. Rather it implies that players aren’t on the same page with each other. That’s the real crime of a severe imbalance of narrative power. It’s not like a GM with unlimited authority can’t tell a good story all on their own if they’re good at it. It’s more that the game isn’t honoring everyone in the group. If collaborative storytelling is what we’re after, a good system should foster communication and negotiation between all the players. All too often player and GM intentions alike completely miss each other like ships in the night. Mismatched expectations and mistakes happen because people didn’t understand what their friends were going for. By contrast, when you really listen to other players and understand the intended fantasy they have in their head, you can help push in the same direction and help them realize their idea. It feels awesome when you manage to do this.

Advice columns for D&Dlikes are constantly telling players of this need to communicate, but the reason they have to tell them is because the game doesn’t force them do it. In fact, the game encourages players to keep secrets more than anything, and those can be dangerous to players’ ability to get on the same page with each other. It’s not the fact that players don’t behave as planned that makes for bad stories. It’s the implications of that mismatch that cause players to clumsily step on each others’ toes and foil each other, often by accident.

And in all of this discussion, I guess I’m a little confused as to why you don’t think a storytelling game (as I define it) could give you the same level of investment as a D&Dlike. It varies by game, obviously, but often these games have you playing just one character and exploring the nuance of their interactions. The system’s definition for character (stuff that goes on your character sheet) informs the types of interactions that they are likely to engage in and helps to push you to discover that part of the character. For example, the very act of playing Annalise has players essentially doing a deep-dive into the character’s psyche and their inner demons. There’s loads of character investment in these games. In fact, Annalise is named after one of the author’s own characters that he was so invested in that he wrote an entire game just to explore her inner conflict.

So I guess I don’t see why D&Dlikes should do character investment any better than other RPGs. Can you feel a sense of investment while playing D&D or LARPing or whatever else? Sure. But it’s ultimately something you paste onto the game on your own. I’m not saying your friends were looking for an excuse to fight with foam swords. It’s the other way around: your foam swords became an excuse to tell stories and invest in characters. You didn’t need to use foam swords, nor did you need to invest in your characters – the two aren’t intrinsically linked. It’s the same way in D&D: players who want to connect with characters might happen to play D&D, but you can successfully play it without roleplaying at all, as John Wick writes here. The same can’t be said for storytelling games – they don’t make sense any other way.

I’ve enjoyed this entire series, but the personal storytelling in the last installment is near the top of the form. Remarkable work. Thank you for sharing it.

And not quite so surprisingly, this is exactly my experience.

Playing DnD has always resulted in more murder-hobo behaviour than any other system I have ever played.

4E was my favourite DnD, because it was completely honest about being a tactical combat board game, and was very good at that.

Thank you for putting it into words so succinctly.

I have a certain fondness for 4th edition, for similar reasons. In fact, here’s a fun fact regarding 4e and the making of my article series (apologies if you already saw this on Twitter).

In making the text collage for Part Four: On Narrative Power, I read the DMGs for different editions cover to cover, looking for phrases that amounted to “You’re in control, Mr. God-Emperor.” I got lots of juicy quotes, but the DMG I had the most trouble finding good ones for was…

4TH EDITION!

And I have a theory on that. 4th edition was characterized by two things, in my mind: making the capabilities of characters much more explicit, and presenting those capabilities to the players unambiguously. All you had to do was read the power card on the sheet, and each one told you exactly how it worked. I think a lot of old players rebelled against 4th edition because it felt too explicit. They were used to doing whatever they wanted and making their DM figure it out. Of course, doing so puts still more power into the hands of the DM, and everything becomes about the DM’s opinion all over again.

But 4th edition took that away! Now that player abilities are explicitly defined, you don’t have to ask for the DM’s permission anymore. These rules are a much better prepared “player defense attorney” than usual, and they brook no argument: “He gets to do 1d8+5 and push one square, your honor.”

The opinion article I link to in this article totally trashes 4e, and the comments go on for YEARS. One complaint that gets brought up repeatedly is that there’s no “roleplaying” in 4e. It’s a strange complaint to some, until you realize what they’re talking about. These are people who’ve been playing since the beginning, and many of them didn’t like 3e or 3.5 either. They were used to the fact that there WERE no rules for crazy weird stuff that you wanted to do, and you always had to ask the DM. They considered this “roleplaying.”

To me, this really clinches the idea that within the D&D community, “roleplaying” is a code word for “Doing things not in the books.” It’s no surprise that as this tradition was passed down to future generations, all of the free-form story stuff that the new generation was doing became “roleplaying.” But you can still do all that story stuff in 4e! So why are all the grognards still so convinced there is no roleplaying in 4e?

I have a suspicion, partially confirmed by the stories told in that comments section, that those people are disproportionately if not entirely made up of DMs. Why would they in particular be upset by the lack of “roleplaying” in 4e? Because that takes away some of their power! They like having the final say in how things are going to go at the table, and that’s a lot harder to do when the abilities are so unambiguously worded.

I also have a suspicion that the designers of 4e were doing this on purpose. I think they may have wanted players to have more agency at the table and understand just what they were entitled to. They may have had concerns over how whimsical the power of the DM was in previous versions.

Which brings us to the 4th edition DMG.

It’s actually quite hard to find phrasing in the book that encourages DMs to take control. It gives a lot of floofy advice, and there’s some stuff about differing styles, but rarely if ever does it stroke your ego with “YOU’RE THE BOSS.” The language of 4e was much more friendly and much less authoritarian than any other edition. I think on some level, the 4e designers had it in their heads that the rules were there to serve as a moderator between player and DM. In keeping with this, the rules were made much more explicit to serve that purpose.

Ultimately, DMs still have roughly the same amount of control over everything as in any other edition, but in 4e they had to contend with a lot more “rules lawyering,” as players were appealing to explicit rules rather than interpretive reasoning. But for the bad reputation that the phrase “rules lawyer” has, you have to wonder if the real reason DMs don’t like it is because that means they don’t always win.

Thanks for reading!