Hey everyone, it’s that time again: the year when the grandest of all grand-strategy games plays out involving every single person in America. What game, you ask? Why, it’s the game of Democracy®! In development since 1787 and with a larger concurrent player base than even League of Legends, it’s one of the longest running and most popular games of all time. And here we are in the midst of the latest season. What an exciting and wonderful time to be alive!

But now that the game is on, what’s the best way to play it? Democracy® is a challenging, high-stakes game with some very tough opponents. If you want to come out on top, you’re going to need a strategy. Fortunately, there’s no shortage of people with ideas about the best way to play, and they’re definitely going to tell you all about them. In fact, there’s one strategy in particular that’s in vogue this season, and it has everything to do with wasted votes. That sounds pretty serious. Can a vote really be wasted? Maybe we can use game theory to find out how well this strategy holds up. Let’s try.

The Big Two

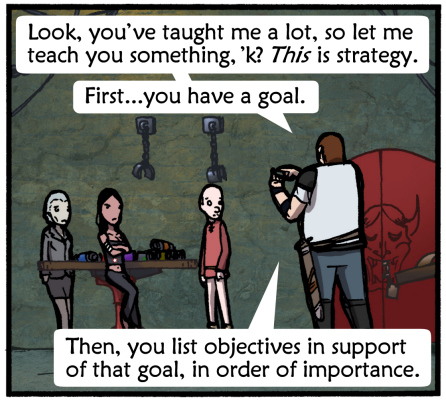

First let’s see what this strategy (I’ll call it Big Two) even says. The Big Two strategy maintains that only two candidates actually have a chance at winning, and therefore to vote for anyone other than those two is to throw your vote away. Proponents of this strategy tend to promote it to undecided voters, or voters who support a third-party other than the leading two candidates. Now, to know how good a strategy is, we first have to understand and clearly state its goal to see if it meets that goal.

So what is this strategy’s goal? Maybe it’s: “Vote for a winning candidate.” But no, that can’t be right, because then the optimal move would be to vote as late as you can and cast your vote for the current leader, and that’s definitely not what Big Two proponents mean. We need a goal that specifies a preferred candidate. But the problem there is that the target audience for the Big Two strategy already have a preferred candidate, one who isn’t one of the big two, or maybe don’t like any candidates at all.

Proponents of Big Two usually frame the goal as “Vote against the other guy.” But any vote for any candidate is a vote against all other candidates, it just isn’t seen as an effective vote against a particular candidate unless it’s cast for the other one of the big two. So does that make the goal “Vote for me,” where “me” is the person suggesting Big Two? But that’s not a goal of the voter, and the voter is the person we’re discussing right now.

So how can we properly frame the goal of the voter? What does the voter get out of this strategy? Considering that the voter isn’t going to vote for the candidate they wanted, it seems like the only real value a voter gets by adopting Big Two is “Don’t waste my vote,” which makes that the goal. So now that we know what the voter wants, let’s analyze how effective Big Two is at accomplishing that goal.

Wasted Votes

First let’s define what it means to waste your vote. Big Two proponents describe a wasted vote as a vote for a candidate who doesn’t win – that’s why they suggest one of the two leading candidates since they’re most likely to win. But what happens if that candidate loses after all? You could still end up wasting your vote, even using a strategy tailor-made to minimize vote wasting.

And that’s only half the story. Another way you can define a wasted vote is “a vote that didn’t affect the outcome.” That means a candidate can actually have too many votes. If you vote for a candidate who wins by a margin of 10%, that means that just under 10% of voters also wasted their votes. In a winner-takes-all election, a candidate very often doesn’t need every single vote cast for them. In that case, 10% of the voters could’ve switched their votes to someone else. But which ones? Any one of them, or maybe a few thousand, could’ve voted otherwise – it’s only once the 10% margin disappears that suddenly no one can switch anymore. Until that moment, any single person could be said to have wasted their vote.

As you can see, not wasting your vote is extraordinarily hard. Since people vote in isolation from each other, they have imperfect information about what the final results will be. Therefore if you want to not waste your vote, the best and really only thing to do is to just cast a vote and hope that you turn the outcome. But the odds of that are astronomical. According to a mathematical analysis, each vote has an estimated value of 0.00000079% of the total. The chances that everything will come down to your one vote are so remote, they’re not worth considering. So you can’t really approach your turn at the game with the expectation that your vote will matter in the strictest sense, because that would be akin to winning the lottery. So that would mean that, deep down, 100% of people take their turn expecting to waste their vote.

But surely that can’t be true! Without any votes, nobody would win any elections, so they have to count for something. And that’s true, they do. It’s simultaneously true of Democracy® that all votes add up to a total that determines everything, and also that any single person playing could be said to have wasted their individual vote. So is it a paradox? What do we do? Is Democracy® doomed?

No, Democracy® isn’t doomed, and its foundational rules are more solid than you might think. But the idea of “wasted votes” is a faulty way to look at how the game is played, and it unnecessarily stresses us out. The flaw in our analysis here isn’t the strategy of how the game should be played – it’s who the players are. Because in all likelihood, you aren’t actually a player of the game of Democracy® at all.

Who Are the Players?

If you want to find the players in Democracy®, a likely place to look are people who have the ability to affect the outcome. So the presidential candidates are players for sure. After all, they undertake a lengthy campaign season trying to affect who votes what, and the things they do throughout the course of that season can vastly affect the outcome. It’s a pretty complicated game of strategy as they vie for the win, each trying to capitalize on each other’s mistakes and adapting to a changing political situation.

But there must be more players than that, right? We don’t have to look far: candidates have entire teams of fellow politicians that support them as part of their campaign. Outside the office-holding political realm, there are talk show hosts on television, radio, and the internet. They make careers out of steering the game as much as they can, even in the off-season. Celebrities and TV/movie stars also get in on this from time to time, giving their candid political opinions or calling out specific issues. University professors, religious leaders, union officers – you can imagine pretty much anyone with an audience, and they’re likely playing the game to some degree.

So what does that make you? Well, you’re one of the members of this audience or that demographic, a member of the voting body to be influenced by some player or other, probably by many players. And what you do at the end of the game reflects the results of the combined and opposing efforts of all the players.

In other words, you are the score.

As weird as it may be to think of it this way, the act of voting does not ultimately give you any agency over the results of an election. It’s only as a group that the votes have any impact or meaning. So it doesn’t make any sense to analyze a decision tree or try to formulate a strategy for the individual voter – no single one of them will matter, and all voter choices are practically indistinguishable. So you aren’t an acting agent in the process – you are a result.

Who’s Playing Who?

That doesn’t mean you can’t do anything to influence the results of the game – it’s just that merely voting isn’t a particularly effective way to do it. Influencing an audience of people (and thus their portion of the final score) would yield better results. As you do that, you become more of a player of the game. Your impact as a player is measured by the size of your audience, ranging from an occasional Facebook post to a YouTube commentary channel or maybe more.

But this distinction between player and score implies an interesting relationship between the two. By definition, a player in a game has a goal, and things that a player does in the game are in support of that goal. But that goal is theirs and theirs alone. And what’s perhaps strange is the fact that in this particular game, the only relevant action is talking to and influencing other people, people who may not share that goal. So really the player of Democracy® is playing the people. Not playing against them, but using them to achieve a goal of their own.

There’s some pretty big implications here. Someone addressing you as a group or bloc of voters doesn’t really know you or what your values are, but they will tell you how to vote, based on their own values. Now maybe that’s okay: maybe you share those values, and they give you a clearer picture of the political spectrum. Just don’t forget that a player of Democracy® has their own goal, one that doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with you.

So with this revised understanding of the game, let’s finally return to the Big Two strategy. This strategy quite clearly doesn’t work, at least when you view it in terms of value provided to the voter (aka: the score). A voter who doesn’t want either of the big two candidates still gets one of the big two candidates, and the vote itself was assuredly “wasted” anyway. But the strategy does serve the interests of the player of Democracy®. If the player manages to sway enough of the score, that player gets what they wanted. Now we clearly see the reason why famous players keep proclaiming the virtues of the Big Two strategy: it’s a strategy for them, not for you.

What About You?

So how should you vote? If you’re nothing more than a tiny score component of a larger game, and it doesn’t even make sense to think about strategy on your level, is there anything to guide you? Should you do anything at all?

That’s an easy one: do whatever you want. Since you’re the score, you’re in a position to inform every player how well you think they did. You can’t really affect the outcome of the game, but you can let everyone know how much any of it served your interests. Because in a larger sense, the game of Democracy® never ends. There’s always next time, and everything that happened last time informs how it’ll go in the future. A vote for a losing candidate may be a “wasted vote,” but that vote does affect the game in that it’s an expression of your values and how much anyone paid any attention to them.

If enough of the score goes towards someone other than the big two candidates, that can have a significant impact on the players, even if that third candidate doesn’t win. It forces players to confront the reality that their platform maybe doesn’t cut it anymore. Maybe they need to revise their strategy and include some of the third-party talking points if they want your part of the score. Or even crazier things can happen. Like for example, one of the lesser known rules of Democracy® is that if no candidate get 270 electoral votes, no one wins, and the House of Representatives chooses the president instead. If it came to that, who would they pick? It’s all part of the depth and nuance of the potential outcomes of Democracy®. It doesn’t only matter that a candidate wins, it’s how they won, and the circumstances in which they won that can make a difference, especially going into the future.

There’s a place in the game for all kinds of different votes, and they all add up to a pretty complicated conclusion. There’s even a place for no vote at all, as almost half of the scoring pool has decided. Are those bad people? Some players of the game would have you believe so. Some players speak eloquently about your moral responsibility to vote one way or another, or your responsibility to vote at all. But given the reality that any one vote can’t realistically change an election, trying to ascribe an agency to that voter, and hence a moral imperative to them is crazy! It’s naive, and possibly dishonest. Because never forget that whatever they tell you, they’re playing the game and, on some level, getting what they want.

So vote how you want. Vote how you feel. Or don’t vote at all. Don’t let anyone, not even me, make you feel bad about your voting decision. Make your vote your own – it’s yours and no one else’s. You are the score, so embrace it and make it speak as loudly as possible to every player of the game.

And don’t forget to have fun!

Further reading:

How Not To Waste Your Vote: A Mathematical Analysis – Stephen Weese outlines the actual math of voting far better than I could, along with analysis of previous elections.

Frankly, Democracy has some serious design flaws.

I know, right? I mean they definitely need to nerf God Bless America. It’s way too strong for how easy it is to do.

I love Sam but a lot of things about this article pissed me off.

“Don’t let anyone, not even me, make you feel bad about your voting decision.”

I’m a white, able bodied, upper class male, so for me voting is just a fun thing and it doesn’t really matter! All these people who are all up in arms about what these politicians are saying – be it Donald Trump’s racism, Donald Trump’s sexism, Donald Trump’s inexperience, Donald Trump’s xenophobia, or Hillary Clinton’s political positions – I just don’t get why they don’t just chill out and HAVE FUN with the whole dang thing.

I mean, what’s the worst that can happen? Even if Trump wins, gets rid of the minimum wage, overturns Roe v. Wade, reverses civil rights legislation, appoints white supremacist Supreme Court justices, and maybe even starts an actual war – it seems to me that I will land safely on my privilege. So I don’t see what the big deal is!

That aside, I feel like you’re kind of confusing some points and/or contradicting yourself in here a few times. It seems like the “thesis” is “There’s No Wrong Way to Play Democracy!”, but you also say stuff like “the best way to influence an election is to influence people”. Well, “making people feel bad about their voting decision” is part of that. Simply informing each other is absolutely part of the game of Democracy, and that may itself make others feel bad.

“I’m voting for Donald Trump.”

“Really? Did you know he plans to get rid of the estate tax?”

“Eww, what? Now I feel bad.”

My argument is that yes, anything goes in Democracy, but that includes making each other feel a little bad sometimes. Don’t be mean to each other or disrespectful, but absolutely do everything you can to inform yourself and others of what’s at stake.

Wasted Votes – you define this in a really dumb way which allows you to dismiss it. Yeah it’s true, a candidate can get “too many votes”, but that isn’t a problem! People who fear a Donald Trump presidency have absolutely ZERO cares about Hillary getting “Too Many” votes.

In fact, I actually want her to get “too many” votes. I want this election to be a landslide of historic proportions, because to me that would say that we are, as a society, roundly REJECTING the worst parts of our culture (which have all manifested into Donald Trump).

When people ACTUALLY talk about wasted votes, they’re talking about voting for 3rd party candidates, who have no chance of winning. That’s what makes it a wasted vote and that is not at all silly. (In case anyone would respond with: BUT IF EVERYONE voted that way, the 3rd party candidate would win – yes, and if everyone gave to charity we wouldn’t need social programs, and if I had wings I could fly!)

“There’s even a place for no vote at all, as almost half of the scoring pool has decided.”

Actually only about 25% of people who don’t vote would say they “decided not to”. Most are just too busy or disabled or totally unaware. They don’t have time, money, or education to do stuff like write long articles on all manner of topics like you and I do. Weird, right?

I see you’re already playing Democracy®. Good for you!

As for the way I define wasted votes, I’m defining it in the mathematically correct way. Defining wasted votes in the way that you do only makes sense if your goal is “Don’t elect Trump.” If that’s your goal, then Big Two is maybe good advice. But mathematically, Trump will or will not get elected with or without your individual vote. So with regards to results, it actually doesn’t matter who you vote for.

Now it sounds like your goal is “Landslide loss for Trump,” in which case you’re certainly acting accordingly. You’re going to need a lot of help to accomplish your goal, and it’ll take supplanting many other people’s goals for yours. Good luck!

Well written and entertaining! Thanks for this, Sam!

Nice. Fairly compelling argument I think, and an amusing way to think about it (esp re: “score”).

I’m glad you think so! If it interests you, definitely check out the Stephen Weese article at the end, as it gives more background to that “weight of a vote” number I used. Thanks for reading!