(This is part of the series ‘D&D: Chasing the Dragon.’ Read more from the home page.)

“Let me tell you about my character.” The seven most dreaded words in the geek lexicon.

When you hear them, you know you’re in for a monologue of context-free adventuring, probably a description of their class and magic items, and possibly an explanation of how they broke the game with this weird combination of feats and class features, as well as what they killed that made their DM super mad. You’ll sit there and nod politely as you try to make sense of their disjointed shenanigans. After all, if you endure this, they might be willing to nod politely when you tell them about your character!

Elsewhere in the world, someone else says to their friend “You’ve gotta hear about this show I’m watching!” This person starts talking about the characters and who they are, what they do. And the other person listens. Interested. They might ask questions about it, compare it to shows they know. If they’re into that kind of story (or sometimes even if they’re not), the conversation might even end with “Yeah, I gotta find time to watch that!”

What’s the difference here? In both cases, they’re both talking about characters in a story that they’re enjoying. But why is it that passing acquaintances can successfully talk about television as a topic of interest, but people in the same community with a common interest in D&D just loathe that conversation?

There’s a lot going on there, but a significant reason for it is because of what’s being described. And I really do mean “what” – not “who.” D&D, when used as a guide for good characters, really has a way of steering us away from personality traits, faults, foibles, all of the things that make characters appealing to people. Sure, you are attached to your own character – you made it, after all. But when it comes to making characters that other people can connect with, D&D lacks anything remotely resembling what most would consider to be actual “character.”

Who’s Who

Good characters are the building blocks of a good story. To connect with a story, we need to connect with its characters and their struggles. In order to come alive, characters need to have traits we recognize as human traits, and the more human they seem, the closer of a connection we can develop with them. Often times, characters will also represent an idea or principle that comes from human culture, and they can even become vehicles for our values.

If RPGs are a storytelling medium – as many players take them to be – it’s important for RPGs to make good character frameworks paramount in their design. How do we get there? My introductory article began by discussing Star Wars, so let’s return there for a moment. Red Letter Media features an exhaustive (and highly recommended) review of the Star Wars prequels by Mike Stoklasa, playing the persona of Harry Plinkett. He does an outstanding job explaining the shortcomings of the films in simple terms, and one part of his review has a particularly salient lesson for us, something I like to call the Harry Plinkett test.

The test is simple: describe the character without discussing how they look, what they wear, or their role or profession in the story. In other words, tell us who the character is on the inside when you strip away everything surrounding them. That’s a crucial distinction: we’re concerned with who the character is – not what. There are many droids in Star Wars, but it’s not until I start throwing around words like “prissy,” “high-strung,” “worrywart,” or “puffed up” that you know that I’m talking about C-3PO. Ideally you could transplant the character to another space and time, and they would still be recognizable as that character. The Harry Plinkett test has a way of honing a character in terms of how human that they are.

Click here to watch a clip of the Harry Plinkett test in action. Watch as character descriptors freely stream out as people describe characters from the original trilogy. Watch them independently arrive on synonyms or even the exact same words. Now, that’s a strong character! Then they’re asked to describe characters from The Phantom Menace, and… deafening silence. It says a lot about why people didn’t like the prequels when something so foundational as the characters are failing right out of the gate. Qui-Gon Jinn may be a Jedi, a master even, a diplomat, all manner of things. But when you take away what he is, you’re not left with a whole lot for the audience to connect to.

What’s What?

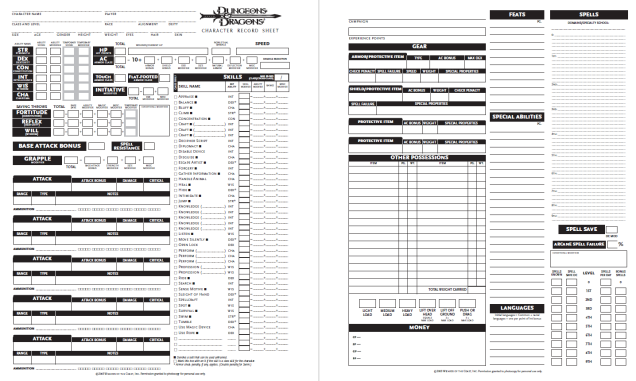

So how does D&D do on this front? All you need to do is take an honest look at D&D character sheets throughout the years, and you’ll notice a striking trend: there’s an awful lot of “what” and not a lot of “who.” There’s stuff like Hit Points, Dexterity, Fortitude, Attack Bonus, on and on it goes. There’s plenty of space here – anywhere from two to four pages worth – but huge swathes of it are dedicated to documenting (in excruciating detail) all of a character’s physical abilities. You’ll find everything from their combat style to their expertise and knowledge to the equipment they carry. Is this the kind of stuff you’d tell people about a favorite film character? The fact that he carries a gun?

But pay close attention: everything on this sheet is a signal for what the game thinks are the most important parts of characters. Every required blank represents a primary way you will be interfacing with that character. What sort of sense would a person get of who your character is if they only read the character sheet? They might start with your class, which is the very backbone of the character. The class defines your collection of superpower-like abilities that coalesce the character around a fantasy stereotype. They’re meant to capture the essence of fantasy favorites from beloved works of fiction.

But what part of those characters does D&D deem most important? Invariably, their method of murder. Do they have a big sword or a little one? Do they shoot fireballs or arrows? The character’s class is a primary definition of the character, but it doesn’t really do much for the essence of the character. Is Luke Skywalker memorable because he swings a laser sword? Plenty of prequel characters do that. Or is it because he’s a simple farmboy caught up in an adventure he didn’t ask for, but nevertheless bravely fights for what he thinks is right? Focusing on how characters fight instead of why they fight is all wrong. It captures the wrong parts of the fantasy archetype, and leaves only a hollow shell.

Now let it not be said that people can’t turn hollow shells into good characters. Let it not be said that no players find it appealing to project character onto the void left by D&D. Let it not even be said that there are no character clues to be found in the thick layers of “what” the character is. After all, in Star Wars the distinction between blaster and light saber is framed as an ideological choice: where one is portrayed as haphazard and careless, the other is portrayed as elegant and humane. It’s possible to derive “who” from “what,” and many players have become quite used to doing just that.

But remember what I said about Rule Zero: if it’s something you have to bring to the table, the game absolutely does not get credit for it. If you’re good at developing characters already, it doesn’t matter what game you play, you’ll do just as well. And if you’re not so good at making good characters? D&D doesn’t have much on offer to help guide you. The assumption is that all that story stuff is something external to the game, something that you have to do on your own.

And don’t be fooled by blank spaces on the sheet where you write in whatever you want. Unless the game has a rule for what you write down, it’s not an important trait as far as the game is concerned. You’ll start to see this in inaction in later editions, namely in idle categories like “Personality Traits.” You might think that it’s a prompt for your creativity, but chances are that whatever you put there, this will be one of the few times you think about it at all. Unless something forces it to be a part of the game, it’s likely doomed to sit forgotten while you continually roll dice on attacking, casting spells, sneaking around, all the character stats that actually matter. It’s no coincidence that many players leave the personality space blank – it’s not required that your character have personality. It is required that you keep track of their wealth, which gets twice as much space on the sheet as personality does.

Even for people who do fill out the intangibles, many don’t consider that in order to roleplay a character, they need to care about how they are perceived by their fellow players. Just because I write down a personality or a backstory doesn’t mean that anyone but me knows what that is. With no rules to prod those things out into the light of day, they’re likely to stay locked in the player’s imagination. Without a way to enable players to communicate to each other the parts that are truly character, the player’s focus is pretty insular. Without a system prompt to connect the characters, players tend to fall back on “traveling companions that met in a tavern.” Without help, you’re left with a bunch of D&D players who want, but fail, to tell you about their characters.

Simply put, making a good character and fostering relationships between them isn’t a prerequisite to playing the game. It’s at best an optional exercise for people to explore on their own before the game pats them on the head and says “Yes, that’s very nice, dear. Now how much damage does he do with a longsword?” For the person who needs a little help with character development and story arcs, D&D has nothing for them. The game promises the experience of being adventurers, and it definitely delivers on that promise. But with no personhood behind them, characters are little more than murder hobos, looking for the next group of canonical bad guys to use as an excuse.

How to Who

When it comes to character creation, long-time players of D&D are quite accustomed to a dichotomy: on the one side you have the mechanical part of the game with all of its statistical minutia, and on the other side you have actual character – personality, history, maybe a portrait, all the stuff that typically earns you some bonus XP. On some level, players are aware that true characterization is something you bring to the game yourself. Not only that, but many of them assume this neutral indifference is the natural state of RPGs. Isn’t character and roleplay just a free-form exercise best left to the player’s best judgment?

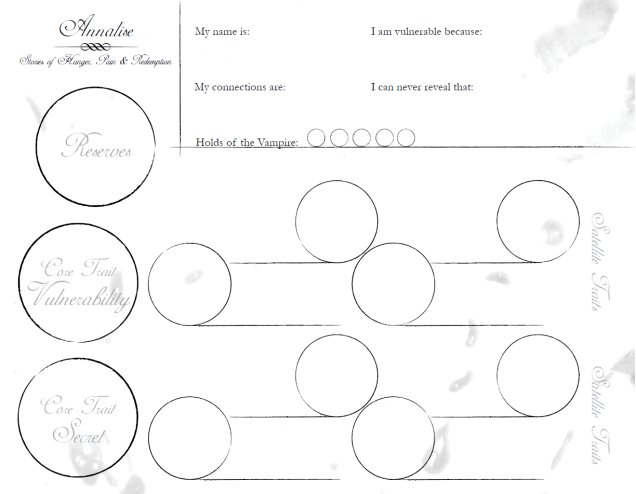

Not if you want a game that’s specifically about roleplaying! It’s entirely possible to make the very act of playing a game synonymous with characterization and growth. As an example, let’s look to Annalise by Nathan D. Paoletta. Annalise is an RPG about vampire stories. Players play not as vampires themselves, but rather the hapless victims that a real or metaphorical vampire might stalk. As potential victims of the vampire, these are characters with emotional vulnerabilities the vampire will exploit.

This is explicitly codified into the rules! Right out of the gate, characters are created with just two Core Traits: a “Vulnerability” which details the character’s emotional weak-spot, and a “Secret” which the character can never let anyone find out. Each of these are authored by players rather than chosen from a list. These two things help define who the character is and what their story arc will be throughout the game.

In the course of play, players begin introducing “Satellite Traits” that will help the characters get what they want during conflict resolution. Each Satellite Trait must be directly tied to one of the two Core Traits from the beginning, and each additional one shows us a new facet of the character. A character whose Vulnerability is “My husband committed suicide and I don’t know why,” might have the Satellite Trait “I emotionally keep my distance from people.” This is a useful Satellite Trait to have in a story about a vampire who lures in unsuspecting prey!

As the story continues, players gain and use more Satellite Traits which surround the two Core Traits. With each new Satellite Trait, the character further emerges and becomes a richer expression of their controlling idea. This is especially compelling in the case of traits that are derived from the character’s Secret. Satellite Traits are public knowledge, but the Secret from which they spring is known only to the player who owns it. So from the perspective of the other players, each Satellite Trait is surrounding this negative space, giving clues as to what that character might be hiding. The more traits there are, the stronger their collective suggestion, and players become invested in the other characters, wondering what the Secret might be. This culminates in the eventual reveal of the Secret, a big moment in the story that ties them all together, and also provides the player a big boost in a single conflict.

There are other big moments, too. In the second half of the game, these Satellite Traits that the characters have been using the whole time can be suddenly “flipped.” A flipped trait becomes the opposite of what it was when it started, and becomes a pivotal moment in the character’s growth arc. “I emotionally keep my distance from people” could suddenly become “I’m fiercely loyal to those who break through my defenses.” A flipped trait is permanent and must be immediately justified in the narration of the story. Watching such an evolution take place in the moment, watching an aloof and closed-off character finally form a close connection to another, creates a powerful sense of climax for the whole table, and is again accompanied by an appropriately large boost for that character in the current conflict.

Annalise doesn’t relegate characterization and development to an optional exercise that the DM occasionally rewards you for doing with an XP cookie. Rather, characterization and the driving of personal story arcs is the very definition of play – if you’re not doing that, you’re not playing Annalise! Every rule, every spot on the character sheet, every facet of play says in no uncertain terms: “This is what we’re doing.” The game points the way for your creative energy and funnels it into productive places for the art of character design.

D&Detail

It’s striking to me watching the uninitiated D&D player sit down with the game for session number one. This player is often coaxed into the game with the promise that it’s a game about telling stories, it’ll be easy, we’ll help you! And then the player sees the character sheet for the first time. Often there’s a look of bewilderment, perhaps intimidation, even lethargy. What does all this stuff mean? Why is it important? What does this have to do with stories?

‘They just don’t get it yet,’ the experienced player assures oneself. ‘They’ll figure it out eventually like the rest of us did. Building a character is important, because if we don’t have all these tiny details, how will we know what kind of person they are? One day they’ll see the character sheet for the rich tapestry it is!’

But the tapestry, if one exists, certainly doesn’t exist on the sheet. For as much fine-grain detail that the game requires, that alone doesn’t distinguish a character very far from another. No, the tapestry exists in the imaginations of the players. That’s where a creative spark begins, and that spark informs the entire creation process. The character sheet is just a record of something that already existed before the game came along.

Moreover, a character sheet is also a tool. If the game is about storytelling, then a good character sheet should ask leading questions to help the player more fully realize the potential of their creative spark. Precisely what a character sheet chooses to record is suggestive of its values. The questions it asks serve as a filter for the potential character. And the more that the game actualizes your answers to those questions within the system, forcing them into the game, the more weight those questions carry.

The substantial questions that the D&D character sheet asks the player are ultimately not very productive for honing a creative spark. And the constrained scope of acceptable answers to those questions has a way of limiting that spark to a narrow set of stereotypes. For as many questions as the character creation process asks, for as many combinations of stats, feats, and armor are possible in the game, they all tend to resolve down to about the same thing: a guy that can kill stuff.

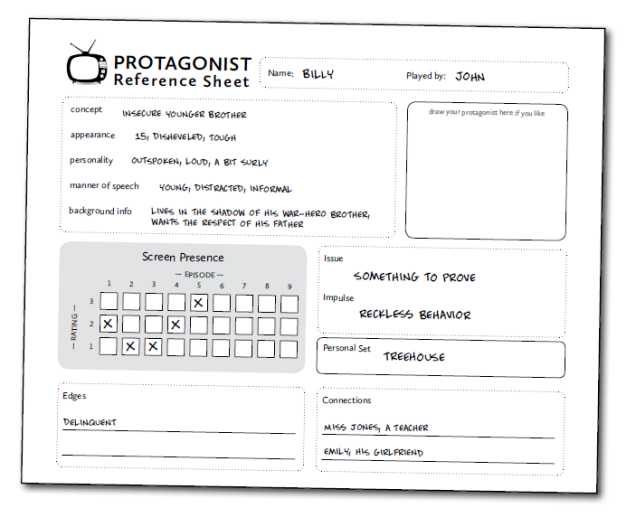

But consider another game, Primetime Adventures by Matt Wilson. Primetime Adventures’ character sheet features far fewer blanks, but the questions are more broad, the answers more open-ended. They concern things like the character’s background, what they struggle with, their negative impulses, who they know, and what they’re good at. Whatever your answers, each one matters within the system, and will come up in the story over and over again.

Of particular note here is that a character’s strong points aren’t rigidly defined, but are loosely encapsulated into their “Edge.” An Edge represents a whole package of intangible abilities and skills the character can access, all of which are boiled down to just a word or two. Again, an Edge isn’t chosen from a list, but invented whole-cloth by the player. And the Edge could be anything. A brief player discussion to define the general boundaries of the Edge is enough to portray an entire range of possible scenarios in which the character would excel without having to write down each and every one of them.

Meanwhile, D&D is stuck documenting out exactly how far you can move in a turn, the precise damage expression of your attack, the amount of arbitrary damage units you can take in a fight, which skills out of a game-approved list your character is good at and a granular scale of how so, what specific spells you can cast and how often, a sanctioned list of all of the mechanical things your class can do, how much weight that you’re currently carrying and how that affects you, your push/drag/lift limits…

D&D gets so lost in the details of a character that there’s scarcely room for anything else on the sheet, in the rulebook, even in your head. If Primetime Adventures were in charge of a fantasy story, you’d just write “Rogue” in your “Edge” blank and that would be good enough. Are you doing a roguey thing? Great, I deal you out an extra card to help you win this conflict. What’s a “roguey thing?” That’s up to us as players – no need for the game to tell us how our fantasies work!

It’s no wonder D&D outsiders are so put off by those first few moments, and maybe we ought to learn from those moments instead of excusing them away. The way the character sheet forces us to relate to our characters just isn’t the way we relate to our favorite characters in our favorite stories. When we’re watching Leia and company escape from Cloud City in Empire Strikes Back, we’re not concerned with how much ammunition she has in her blaster or what her chance to hit with it is. We want to know if she’ll be able to catch Boba Fett before he blasts off with the carbonite-frozen Han. We want to see what it means to her when she fails.

We want to engage with the character. Everything else is just meaningless details.

My personal opinion: Yes, D&D doesn’t offer much guidance on things that aren’t combat. But maybe I don’t want guidance?

I am pretty sure “Don’t give rules for stuff you could freeform” is actually the best approach in this case. In my experience, the strong narrative rules of a lot of indie-RPGs get boring and/or annoying after 2 or 3 sessions (I haven’t played Analise specifically). You can criticise D&D for not having many rules in this area, but that’s a feature, not a bug.

I’m not trying to defend D&D specifically, but when it comes to character-focused roleplaying, I prefer a freeform-experience over a rules-focused experience most of the time… I prefer strong rules for things that are difficult to do well in freeform, like combat.

This is a pretty common stance when it comes to D&D. There’s this idea that the game is a neutral world-calculator, that is otherwise a blank slate for whatever you decide to do. “That’s the roleplay part, that’s not hard, just let me do whatever I want.”

But you can’t do whatever you want! D&D enforces certain story elements just the same as any other game does. No matter what, you must always make a combat-capable character. Every single one of them is expected to fight things, and that has an impact on your character and story. The idea that roleplaying is “freeform” is a supposition born of imposing character-focused roleplaying onto a game not about that at all. And whether you realize it or not, the game pulls you toward the conflicts that it’s able to adjudicate. I write more about what I call the “Neutrality Myth” in Part Six. The short version is that there is no such thing as a neutral system where you freeform anything onto it. The game has an impact even on the stuff that you think that you’re “freeforming.”

How do I know this? Simply by the fact that you even mentioned “combat.” Why would your “character-focused roleplaying” story need to include fighting to the death? As conflicts in stories go, “…and then someone tried to kill him!” is quite weak. It lacks the emotional punch of a conflict where a character must choose between two bad choices, for example. It lacks the philosophical weight of two characters equally justified in their worldviews finding themselves at odds. They don’t need to punch each other for the conflict to engage us and make us question our own outlooks. Why is “combat” necessary at all? Only because D&D says it is.

On top of that, there’s no reason whatsoever that “combat” is difficult to do well in freeform! The only reason you think that it’s hard is because D&D makes it a big deal who wins and who loses. When someone in D&D runs out of HP, they DIE. Obviously nobody wants that to happen! So everyone tries to avoid it, and if narrated in freeform, it comes off as a hamfisted narration where everyone is invincible, because the alternative is DEATH. Take away the expectation that “combat” is specifically about “killing,” and the play dynamic changes quite a bit. Implement a system for resolving conflicts of ideology rather than conflicts of pure brawn, and you’d be surprised how easy it is to freeform combat in service to the story.

And in contrast to all of that, there’s no reason that “character-focused roleplaying” is easy in any way. Basically you’re talking about designing compelling character arcs, engineering interpersonal conflict, balancing the characters’ story roles, letting the characters fail in meaningful ways, resolving their stories to the fullest emotional potential, etc. This stuff is not easy! If it were, then we wouldn’t have “screenwriters” and “literary authors” as career paths. Just doing what comes naturally is simple enough, but does it really make your story sing?

I’m sorry you had the experience with narrative RPGs that you have. Maybe those particular ones (whichever they were) weren’t that great at helping you with character and story. Maybe you haven’t found the narrative-focused RPG that works for you. But also consider the possibility that maybe those games are actually fine, but your expectations of what it means to be an RPG got in the way. This is also extremely common for D&D players – they get it in their heads that roleplaying belongs to ME, and I get to do whatever I want. And when a game tells them “No, your character does this, because it’s better for the story,” they get upset because they don’t feel “in control” of their character.

D&D players often have issues with control. DMs need to control their worlds and stories. Players need to control their characters. Take away that control, and those players feel like something is “wrong.” Whether or not this describes you, really do your best to take a step back and evaluate how much D&D has set your expectations of what an RPG is “supposed” to be. Often we’re slaves to our preconceptions, and only by truly challenging them can we understand more about the world and ourselves.

There will be more along these lines further in the series, so keep these things in mind.

Thanks for reading!

“But you can’t do whatever you want! D&D enforces certain story elements just the same as any other game does.”

Yes!! Thank you!! I don’t enjoy combat-focused games and killing makes me feel bad even if it’s just fiction. I prefer to tell stories about hard choices made by good people, or bad people working hard to be better. D&D has no room for me. In fact, the game actively punishes me for it and makes it very hard to play the kind of character I want to. Meanwhile, playing games more focused on ideological conflicts, I’ve had an incredible time going back and forth and rolling dice for something that would have been solved by a single skill check in D&D. I don’t really have a problem with a game that wants to be something for everyone, but D&D ain’t it.

Ok, thanks for the reply. Here are my thoughts on it:

Yes, if you don’t want to be constrained to combat-focused fantasy, the case against using D&D for building your characters is pretty convincing, even you are going to be freeforming most of the time anyway.

I agree with D&D that who wins and who loses is a big deal when there is combat. The fact that D&D kind of equates “losing” with “death” most of the time is unfortunate, but I would be having a hard time just freeforming something like that.

Ok, maybe I should have phrased that differently: I am not trying to say that “character-focused roleplaying” is easy, but I personally find it more enjoyable to do it in freeform, at least juding by my experience so far.

“Roleplaying belongs to ME, and I get to do whatever I want.” is a statement I agree with 100%. I actually do think that something is “wrong” when the rules take away control of my character.

I really can’t stress enough that the mentality of “I must control my character” makes it really hard to play other kinds of games. That is but one way to roleplay among many. It’s easy to write it off as “Well, that’s what I like.” But I think internalizing the stuff you like now is really limiting and cuts you off from other great experiences you could have. I’m not trying to say that you’re playing games wrong, but it’s important to acknowledge the limitations of any given approach to roleplaying. That’s what I’m doing with this series: when you evaluate D&D purely as an engine for storytelling, it has a lot of limitations that hurt the stories it tells.

So yes, some games take away control of your character. But they do so in service to a particular experience and story genre. I think you should ask yourself why control over your character is so very important, and then ask why these games would break that principle. Check out this thread of advice for how to properly play Dogs in the Vineyard, and note that these people aren’t making up their own interpretations – they’re simply relaying the rules as written. These rules happen to be such a departure from D&D that some migrant players are liable to get the game wrong because they’re just doing what they’re used to. Dogs in the Vineyard really needs you to break with that and play as written. Only then can it help you to tell the story it’s built to tell.

I know it’s hard to break with old habits – I’ve been there myself. But as the saying goes: “If you always do what you’ve always done, you’ll always get what you’ve always got.” Even if you like it now, are you sure you wouldn’t like something else even better? Please keep reading – there’s more to say on the topic as my series unfolds. 🙂